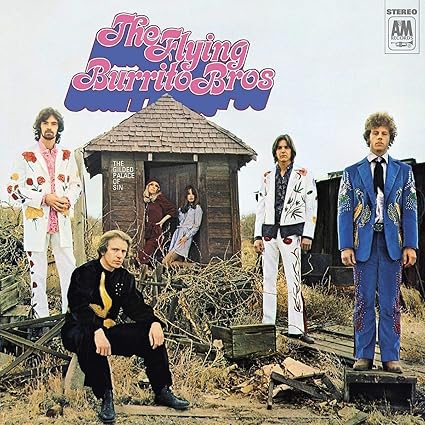

The Flying Burrito Brothers

– The Gilded Palace of Sin

Country Rock didn’t start with The Gilded Palace of Sin, but no album better defines its whiskey-soaked, rhinestone-studded heartache. The Flying Burrito Brothers took the twang of Bakersfield, the swagger of rock and roll, and the melancholy of old soul records and twisted them into something both deeply American and completely their own. It’s dusty but glamorous, ragged but deeply felt—a country album that doesn’t belong on country radio, too rock and roll for Nashville but too honky-tonk for the Sunset Strip.

What makes this album essential is its effortless fusion of heartbreak and rebellion. The pedal steel practically weeps, while the grooves sway with the kind of looseness that suggests the band might fall apart at any second—but never does. There’s a hazy, dreamlike quality running through every track, like it was recorded between last call and sunrise. And yet, for all its grit and late-night desperation, the melodies are undeniably sweet, the harmonies impossibly warm, the lyrics soaked in both regret and defiance.

Few albums feel this lived-in, this true to the restless, searching spirit of American music. It’s not a record that shouts its greatness—it lures you in, lets you get comfortable, and then breaks your heart. Half rock and roll, half country, and entirely out of step with its time, The Gilded Palace of Sin has aged better than almost anything from its era. It still sounds like the past, present, and future of country-rock colliding in a neon-lit desert bar.

Choice Tracks

Cosmic country wasn’t a thing before this record, and honestly, nobody ever did it better. “Christine’s Tune” sets the stage with Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman harmonizing like they were born in the same holler, even though one was a trust fund kid and the other cut his teeth in bluegrass. Sneering lyrics about a dangerous woman, a Bakersfield-style shuffle, and Sneaky Pete Kleinow’s steel guitar twisting through it all like barbed wire in the wind—it’s country, but not the kind you’d ever hear on Nashville radio. Then “Sin City” drops in, a slow-burn lament that feels like a eulogy for America itself. Parsons’ voice is all ghostly heartbreak, and Kleinow’s pedal steel doesn’t just weep—it howls, like it knows the doom he’s singing about is already here.

“Do Right Woman” should have been sacrilege—two cosmic cowboys trying to take on Aretha Franklin? But instead, they turn it into something tender, damn near reverent, like they’re begging for redemption they know they don’t deserve. And then there’s “Dark End of the Street,” the cheating song to end all cheating songs, delivered with so much quiet devastation you half expect the record to crack under the weight of it. But Gilded Palace isn’t all heartache and regret—”My Uncle” is pure hippie rebellion wrapped in a honky-tonk romp, proof that Parsons could slip counterculture into a country song without blinking. And “Hot Burrito #1”? That’s the gut punch, the song where Gram sings like his heart’s been ripped out and he’s just standing there, bleeding all over the floor.

By the time “Hippie Boy” closes things out—half-spoken word, half-drunken gospel—you realize The Gilded Palace of Sin isn’t just an album. It’s a beautifully broken dream of what country music could have been if Nashville hadn’t been so afraid of long hair and psychedelic dust. Parsons and Hillman weren’t just playing dress-up with rhinestone suits and Nudie jackets. They were carving out a whole new sound, one that still echoes through every band that’s ever tried to bring some soul into country music without selling their own in the process.