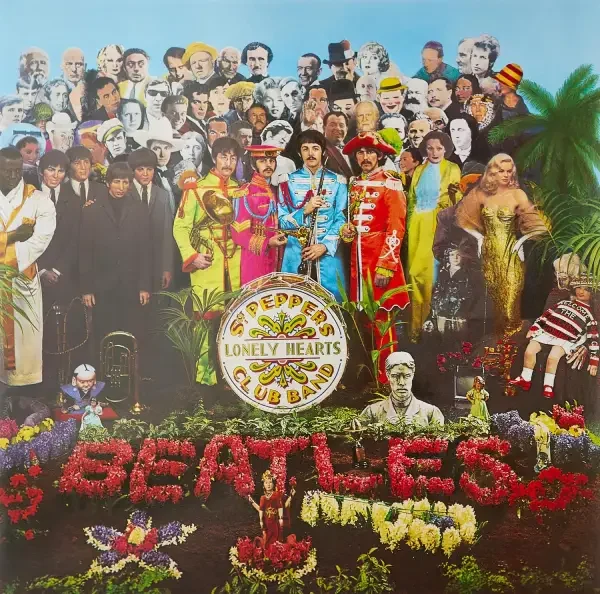

The Beatles

– Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

There are albums that break the mold, and then there’s Sgt. Pepper. In 1967, The Beatles didn’t just change the game—they torched the board and built something entirely different in its place. This isn’t just a collection of songs dressed up in brass and psychedelia. It’s a leap into character, color, and sound—a vivid escape hatch from reality, with the band playing not as themselves, but as a vaudeville fantasy version of themselves. They weren’t trying to show off. They were bored, brilliant, and a little fried from the mania. The result: a record that still manages to sound like a well-aimed dare at what rock music could become.

There’s a certain joy in how Sgt. Pepper sidesteps any obligation to stick to a single genre or tone. The album spins like a dream, but it’s not sleepy—it’s a bright-eyed hallucination, fueled by English music hall, Indian classical, avant-garde collage, and a healthy dose of “what if?” No track feels like filler. Even the oddest moments carry weight. You hear the playfulness in “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!”, the hazy mysticism in “Within You Without You,” the bittersweet sting in “She’s Leaving Home.” It’s showbiz, satire, soul, and sadness all in one rotating stage show. Somehow, it works.

Lennon and McCartney are clearly having a ball, yet they’re also writing some of their most vulnerable and revealing material to date. Harrison finds his footing with cosmic contemplation. Ringo gets his moment with a tune that turned melancholy into something endearing. The band and producer George Martin are painting with sound—throwing tape loops, orchestras, and vintage instruments into the mix like kids in a candy store who never got told “no.” And through it all, there’s this strange cohesion. It doesn’t ask to be believed. It asks to be felt.

Choice Tracks

A Day in the Life

If the rest of the album is a carnival, this is the exit through the cosmic gift shop. Lennon opens with his deadpan surrealism, turning newspaper snippets into existential dread. McCartney answers with a brisk morning routine that feels like a jolt of caffeine. The orchestral crescendos? Controlled chaos. The final piano chord? A full stop and a moment of stunned silence. It doesn’t just close the album—it flattens it into eternity. Chilling, human, and unforgettable.

Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds

Forget the acronym rumors. This is pure imagination filtered through Lennon’s childlike lens and McCartney’s musical alchemy. The verses float like stained glass in sunlight; the chorus punches in with dizzying color. It’s disorienting in the best way—a playground where the swing set might levitate if you stare hard enough.

She’s Leaving Home

McCartney’s voice breaks just enough to make it feel real. This isn’t rebellion. It’s resignation. A gentle orchestral arrangement carries the song while Lennon adds a Greek chorus of baffled parents. There’s no judgment here—just quiet devastation. Maybe the most emotionally direct song on the album.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band / With a Little Help from My Friends

A perfect one-two. The title track kicks open the curtain with a knowing wink, and Ringo’s “Billy Shears” character takes the mic with all the understated charm in the world. “With a Little Help” isn’t flashy, but that’s the point. It’s an anthem of modest resilience and camaraderie that everyone can sing along to, preferably a little out of tune.

Sgt. Pepper isn’t perfect because it’s polished. It’s perfect because it’s fearless. The Beatles didn’t just redefine pop—they showed how weird and beautiful it could be without losing its mass appeal. It’s theater. It’s studio wizardry. It’s a fever dream that still holds up under a magnifying glass. Decades later, it’s not just an album. It’s a signal flare from a band that figured out how to make the surreal sing.